Editor’s note: In the summer of 2012, I did some genealogy on the family of Mona (Blankenship) Carter, a friend of mine. When I ran across James McKinney and his story, I was very moved by the experience that he must have endured. Then it occurred to me that, in a way, it was representative of the hardships that a number of our Marion ancestors endured. That anyone could endure hardships like this in their lives and come out even reasonably normal is truly a tribute to the pioneer spirit. Not only did James “survive” his ordeal, he triumphed over it and because he did, literally dozens of Marion families now exist today as part of his lineage. In truth, this story is about many Williamson county families and their stories.

In the latter days of the 1850’s James H. McKinney, who was born on March 15, 1842, made his way from his home state of Mississippi to the promise of a new life in Williamson County. Having been left an orphan at the age of twelve, like many young southern people in those days, the attraction of cheap and available land in Southern Illinois served as an attraction and he had heard the call.

Decades before, in 1816, a man by the name of Philip T. Russell had built one of the first cabins in the county on Eight Mile Prairie (around current Cambria). Philip’s father was General William Russell who had served alongside George Washington in the Revolutionary War. Philip himself joined the army when he was 16 and took a bullet in his side at the battle of the Guilford Court House which remained in him to his death. Philip had also been on scene and witnessed the surrender of General Cornwallis at Yorktown. When he came to Williamson County from Tennessee he brought his four sons and they settled the Eight Mile area. They built houses near each other which formed what was called “Russell Corners”. It would later become Fredonia post office and a regular stop on the stagecoach mail runs. The Russell family was an extremely patriotic lot and were known for throwing events with bands, BBQ’s and fun to serve as recruitment events to inspire registration in the service of the country.

It was in this atmosphere that James McKinney had temporarily settled in the late 1850’s when he migrated from his home state, taking lodging at the home of John Hinchcliff and his family at Russell Corners.

John Hinchcliff was a natural born Englishman who was carried by his mother onboard the sailing vessel Electra tied up at Liverpool in 1826 when he was 6 months old. In October that year the entire Hinchcliff family arrived at the port of Philadelphia and stepped ashore. His father John Sr. and his mother were both in their early 30’s and had another son William 8 and daughter Martha 4. Two and a half to three years later in 1829, the family had made their way cross country and settled on Eight Mile Prairie in Williamson County. All of the Hinchcliff males invested in their futures and built their homes here over time. In 1837, it is recorded that John Sr. bought 40 acres and paid $1.25 an acre for a total of $50. In September 1840, John Jr. at 20 married a girl by the name of Priscilla Patsy Hampton who was 21. Priscilla was the daughter of James R. Hampton who was a Major in the Black Hawk war of 1832 fought mostly in northwestern Illinois. Fast forward to 1860 and we find John and Priscilla appearing to thrive. They report real estate and personal values equaling or exceeding their neighbors. They also now have 3 daughters and 2 sons ranging in age from 12 to newborn. It was under these conditions that James McKinney found shelter under the roof of the Hinchcliff family while working as a laborer in the field.

The first week of August 1862 brought patriotic celebration to Russell Corners when it was made known that a number of stump speeches were going to be made promoting military campaigns. Neighbors aranged a barbeque in the tree groves. Gabe Cox, a veteran of the Mexican war played a fife and his two sons beat the drums. Men marched and drilled and a greater part of Company G, 81st Illinois infantry was enlisted. On that day, Philip Russell saw one son, six grandsons and the husbands of two granddaughters enlist in the 81st.

When 36 year old family man John Hinchcliff made the decision to serve his country and join the army James McKinney, now 25 accompanied his friend and mentor. They went to the recruitment office in Carbondale on August 4, 1862 and both men were enlisted in Company B of the 81st Infantry Regiment by Capt. Thomas Hightower. On August 26th both men reported for duty and were mustered into service at Camp Anna, located near the current location of Choate Mental Hospital in Anna, Illinois.

No sooner had their training begun at Camp Anna when they were called to Cairo. On October 8th they were ordered to join the army in the field under General Ulysses S. Grant in Tennessee. Their first assignment was garrison duty at Humboldt Tennessee. In May of 1863 they followed Grant’s army to Louisiana and then into the Battle of Bruinsburg in Mississippi. Over the next several months they would participate in several battles in Louisiana and the first attempts by Grant at Vicksburg in May 1864 which were repulsed with the 81st having 11 killed and 96 wounded. In February 1864, James had been promoted to Corporal.

Over the next year they would be involved in several battles and skirmishes in Louisiana and Mississippi ending back at Vicksburg by May 1864. From Vicksburg the regiment was ordered to Memphis, Tenn., and participated in the expedition to and battle of Guntown, Miss.

Confederate Gen. Nathan Forrest set out with his cavalry corps of about 2,000 men to enter Middle Tennessee and destroy the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, which was carrying men and supplies to Union Gen. Sherman in Georgia. On June 10, 1864, Forrest’s smaller Confederate force defeated a much larger Union column under Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis at Brice’s Cross Roads. This brilliant tactical victory against long odds cemented Forrest’s reputation as one of the foremost mounted Confederate infantry leaders of the war. The Union 81st was the first infantry regiment to open fire and continued under fire from 11 A.M. until dark, resisting charge after charge of the enemy, forming the last line of battle some 2 miles in the rear of the first line, closing the bloody drama with a loss of 9 killed, 18 wounded and 126 prisoners, out of a total of 371 men.

Out of the 126 prisoners of war taken on June 10th were John Hinchcliff and James McKinney. Ironically, earlier in the day John had been promoted to Corporal. Out of the numerous POW camps they could have been taken to, John and James were about to engage in a 350 mile journey to the infamous Andersonville Prison in Georgia.

Andersonville, or Camp Sumter as it was known officially, held more prisoners at any given time than any of the other Confederate military prisons. It was built in early 1864 after Confederate officials decided to move the large number of Federal prisoners in and around Richmond to a place of greater security and more abundant food. During the 14 months it existed, more than 45,000 Union soldiers were confined here. Of these, almost 13,000 died from disease, poor sanitation, malnutrition, overcrowding, or exposure to the elements.

The first prisoners were brought to Andersonville in late February 1864. During the next few months, approximately 400 more arrived each day. By the end of June, 26,000 men were penned in an area originally meant for only 10,000 prisoners. The largest number held at any one time was more than 33,000 in August 1864. The Confederate government could not provide adequate housing, food, clothing or medical care to their Federal captives because of deteriorating economic conditions in the South, a poor transportation system, and the desperate need of the Confederate army for food and supplies.

It was under these conditions in June 1864 that John and James found themselves. On February 25th 1865, after eight months of near starvation, diarrhea and dysentery James could only watch helplessly as his friend John slipped away from him into the hands of his maker. Unknown to his loving family, John Hinchcliff had become grave number 12,683 in Andersonville Prison.

On March 15th 1865, in accordance with a prisoner exchange agreement made by Ulysses S. Grant many of the Andersonville prisoners including James were exchanged at Big Black Bridge in Mississippi. Most of the prisoners unable to walk on their own were transported by rail, steamboat and wagon to Springfield Illinois for medical care, debriefing and mustering out of the service. James was released from duty on May 30, 1865. I can’t imagine his anticipation of having to face the Hinchcliff family for the first time or how we would tell them what had become of John.

The 1870 census reveals James living alone at the age of 28 and working as a farm hand at Russell Corners, Fredonia post office. Priscilla Hinchcliff had remarried J.J. Dillard on October 29, 1866 likely to care for her large family.

On March 7, 1872 James married Minerva Jane Dunn whom he had fallen in love with. Minerva’s family owned land around Hudgens Illinois just a few miles due south of Marion and this is where they made their home. By the next year their first child James was born. The children that followed were John 1875, William 1877, Theodore 1879, Lloyd Egbert 1881, Alice 1884, Myrtle 1886 and the last, Ellen in 1888.

On the 27th of March 1874 James filed for a Civil War Pension which he well deserved and later received.

By 1900, the McKinney family was firmly rooted in the area just to the northwest of Hudgens. In 1900, there were still 5 children living at home, James Jr. was now on his own, his brother William had a farm nearby as well as Minerva’s widowed mother and her remaining children.

A 1908 plat map shows J.H. McKinney owning a 180 acre plot of land located ENE of Hudgens. If I’m not mistaken, this probably includes a fair amount of land that is now occupied by Rt 37 south just before you reach Hudgens road. I also presume the Freedom Cemetery to be located on this land or awfully close to it.

The 1910 census tells us that James is now 68 and Minerva is 58. They have two children living at home. Their daughter Myrtle, 24, is a school teacher. Their son John is 34 and helping his father run the family farm.

On April 11, 1914 James passed away at the age of 72. Later that year his wife applied for his civil war pension and later received it. Minerva passed away August 31, 1938.

One of James’ sons, Lloyd Egbert McKinney, had four children. They were Helen, James H. Lloyd F. and Charles L. In 1921 Helen met the mail carrier who worked their route on his motorcycle. They fell in love and in 1922 Helen married Earl Blankenship Sr. founder of E. Blankenship auto parts. Lloyd passed away in 1974.

Their first son James Wesley McKinney became an influential Baptist preacher at Warder Street Baptist church and also served as County Superintendent of Schools, he died in 1950.

Daughter Alice McKinney went on to marry Frank Brown, a descendent of the Dunaway family, and died on December 26, 1951.

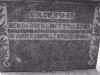

Many of the family, including James and Minerva, are buried at Freedom Cemetery on Route 37 south of Marion app. 4 miles. John Hinchcliff is interred to this day at Andersonville National Cemetery grave marker #12,683.

(Data drawn from Pioneer Folks and Places by Barbara Barr Hubbs; Civil war records on file at Illinois CyberDrive, Ancestry.com, Regimental records, federal census records, civil war POW records, Andersonville National Cemetery Records, and various civil war sites. Compiled by Sam Lattuca on 01/12/2013, revised 02/22/2015)